2 min read

Lucas v. Dayton: Colorado Court Dismisses Informed-Consent Claim Against UCHA

Joe Whitcomb

:

December 11, 2025

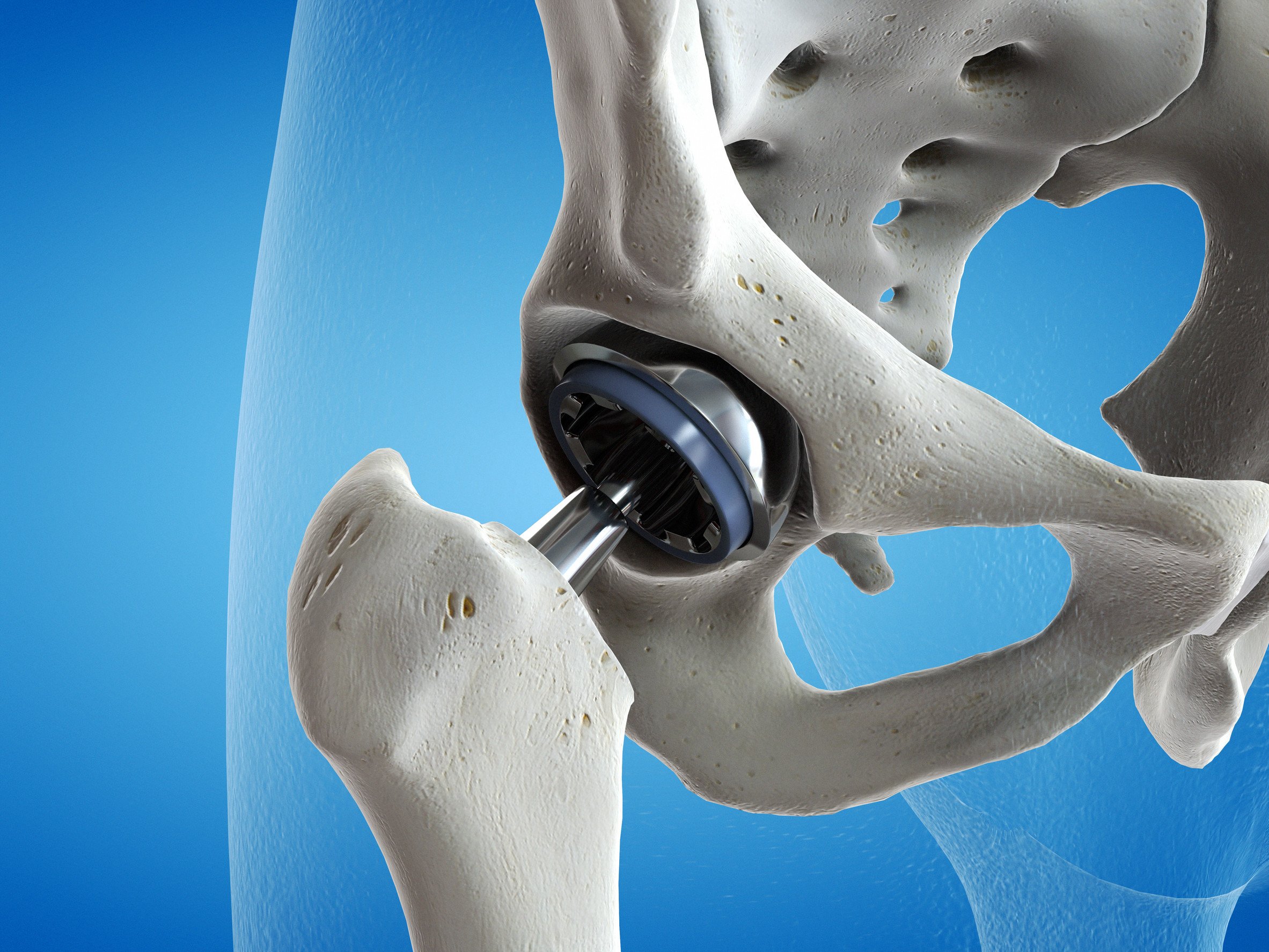

Irma Lucas filed a medical malpractice action arising from a hip replacement surgery performed on January 20, 2023. She alleged that Michael Rex Dayton, M.D., agreed to perform the procedure using an anterior approach but instead completed the surgery using a posterior approach. Her complaint included four claims for relief: negligence and malpractice, battery, fraud, and lack of informed consent. The lack of informed consent claim was asserted against all defendants, including the University of Colorado Hospital Authority (UCHA).

UCHA moved to dismiss the fourth claim, arguing that the complaint did not allege any facts showing that UCHA owed a duty to obtain Lucas’s informed consent or that it played any role in preoperative discussions. The motion stated that Lucas’s allegations referenced UCHA only in the caption and in two brief background paragraphs but did not describe conduct supporting liability.

Standards Governing Motions to Dismiss

Under Colorado’s plausibility standard, adopted in line with federal pleading requirements, a complaint must contain facts that make a claim for relief plausible rather than speculative. To survive a motion to dismiss, the pleading must allege factual content supporting each required element of a claim. A plaintiff must present allegations that "nudge" the claim across the line from conceivable to plausible by showing a factual basis for each essential element.

The court reviewed the complaint to determine whether Lucas alleged any facts showing that UCHA owed her a duty, breached that duty, or engaged in conduct connected to the informed consent discussion.

Analysis of the Informed Consent Claim

The court examined every reference to UCHA in the complaint. Lucas identified UCHA as a defendant on the basis that it was not immediately clear whether the entity had control over staff or physicians who provided her care. The complaint did not describe any specific actions by UCHA, any interaction between Lucas and UCHA personnel, or any role the entity played in preoperative discussions.

The informed consent claim itself alleged that Dr. Dayton failed to obtain Lucas’s consent for the posterior hip arthroplasty. The allegations focused exclusively on the surgeon’s duty and conduct. Nothing in the complaint asserted that UCHA communicated information to Lucas, failed to do so, or had an obligation to participate in her informed consent process.

Colorado case law establishes that the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent rests solely with the physician performing the procedure. Courts have consistently held that hospitals do not owe a duty to obtain informed consent for medical treatment because obtaining consent is part of the practice of medicine. Corporations and healthcare entities cannot practice medicine under Colorado law. Because only licensed physicians and certain other licensed providers may obtain informed consent, an institutional defendant cannot be held liable for failing to do so.

The court reviewed relevant authorities confirming this principle. Colorado decisions have long recognized that only the treating physician bears responsibility for explaining the risks and nature of a procedure. Jury instructions likewise charge the physician with the duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent. Because the law does not impose this duty on a hospital or hospital authority, an informed consent claim cannot proceed against such an entity.

Applying these legal principles, the court concluded that Lucas’s claim against UCHA was legally insufficient. The complaint did not allege any facts that could support liability, and even if additional facts were pleaded, UCHA could not owe the duty alleged because informed consent must come from the physician.

Request for Fees and Costs

UCHA also sought an award of fees and costs under Colorado law, asserting that the lack of any legal duty made the claim untenable. It argued that the allegations failed as a matter of law and that requiring UCHA to defend against such a claim resulted in unnecessary litigation expenses.

The Court’s Decision

The court determined that Lucas did not plead a plausible claim for lack of informed consent against UCHA. Because only a physician may obtain informed consent for a surgical procedure, and because the complaint alleged no conduct by UCHA that could create such a duty, the claim could not proceed. The court therefore granted the motion to dismiss the fourth claim for relief as to UCHA.

Assistance With Medical Malpractice Matters

If you’ve experienced medical malpractice, Whitcomb Selinsky PC handles medical malpractice matters. Reach out to our team through our contact page to learn how our team can assist with your claim.